It’s Time to Throw Out Stereotypes About Aging!

The National Geographic and AARP exclusive study shows that older Americans are redefining their health, defying challenges and living with purpose.

"As you grow older, you will discover that you have two hands — one for helping yourself, the other for helping others." — Audrey Hepburn

In late 2021, journalists at National Geographicmagazine and AARP discussed working together to explore how Americans perceive aging as we emerge from the COVID pandemic. That began a research collaboration focused on asking people like you questions that would probe the full breadth of aging issues — from health and finances to attitudes about happiness, home, optimism and even dying.

To make the study as useful as possible, we posed the same questions to Americans from age 18 into their 90s, to see how opinions vary over the arc of adulthood. More than 2,500 people participated, representing the full range of America’s backgrounds, demographics and ethnicities. Another 25 adults 40 and older participated in in-depth interviews.

Many of the often surprising results of the AARP–National Geographic “Second Half of Life Study”are in your hands. No single sentence can capture the gist of all that people told us, but we can say with confidence that most prevalent opinions and stereotypes of aging were proven wrong.

Overall, the message was refreshingly positive and reassuring. On the whole, life is good, especially for older Americans — especially those over 60. And the person you see in the mirror is far different from the type of person younger generations might think you are.

Here is what you told us about aging today — not only conclusions from the data but also comments from study participants (who shared their first names only), as well as from leading experts on aging-related topics.

Part 1: Health Redefined

Longevity pill? Maybe

The survey posed this tantalizing proposition: Would you take a pill that immediately granted 10 bonus years of life? While around three-quarters of adults across all age ranges said they likely would take such a pill, one interesting finding was that those 80 and older were the least interested. And when the question was posed without an age guarantee, but instead cited the promise of slower aging with extended health, the likelihood shot up to around 85 percent.

“Age is just a number that’s assigned to me,” says study participant Jackie, age 56. “I’d like to live as long as I possibly can and enjoy it, but I don’t want to be old and not be able to function. I want to be healthy.”

'Healthy with conditions’ is the new norm

Conventional takes on physical well-being often are presented as “either-or” — either you’re healthy or you’re sick. But about 2 out of 3 people in their 50s and 8 out of 10 in their 80s are living with one or more serious or chronic health conditions. And despite their arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease or other conditions, 78 to 83 percent rated their health good, very good or excellent.

“There’s a survival benefit to resilience. People can reframe their situation and make the best of it,” says Susan Friedman, M.D., a professor in the division of geriatrics and aging at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. And, she adds, “health is multidimensional.”

That’s how Ruth, a study participant in her 90s, sees it. She still sings in a church choir and plays table tennis, despite using a walker. “Good health is being able to get up each day and do the things that you plan to do, and not dread them,” she says.

Timothy, 51, has a similar view. This study participant has immunity challenges, and a few years ago survived a month in the hospital. Now, he says, “You just wake up in the morning, you eat a handful of pills, and you go about your day. You don’t let it overwhelm your mind.”

With age come ... healthy foods and walking shoes

Perhaps in an effort to delay the day when they face mental decline or lack of mobility, older people are often models of healthy living that younger generations should emulate.

Lillian, who’s in her 70s, avidly reads nutrition labels, opts for steaming or air-frying over frying food in oil (“because frying is not good for you”), takes vitamins and is thrilled that a relative is giving her an exercise bike for her apartment.

Similarly, Robin, 64, takes her three dogs for a daily walk, then heads out again. “I go for another walk with my husband. Maybe we’ll go walking with friends. If the weather is not nice, I go on my treadmill and do exercises over the TV. I see exercise as one way to stay healthy.”

Older people pump even more iron

An impressive 44 percent of people 80 or older say they do strength training — making them as serious about muscles as the youngest in the study. Richard, 70, is an example. “I have a black belt and am trained in hand-to-hand combat, which I started at age 55,” he says. “Before COVID hit, I was still doing CrossFit and kickboxing.” The 80-plus folks’ motivation? Many correctly equate muscle strength with mobility and independence, Friedman says.

The good life equation?

All these new notions about health were reinforced in the study when we asked about what health issues people worry about most. Respondents feared loss of mobility and mental decline far more than life-threatening but less symptomatic issues like diabetes and heart disease. “Even if they have health issues, they’re really worried about: Can I still move? Am I still mentally sharp? Can I still connect with and see my family?” says Debra Whitman, chief public policy officer for AARP.

That’s a powerful message that the medical community, and even family members and caregivers, don’t always hear when advising older people on important health decisions, such as undergoing a major medical procedure. “It shouldn’t be treatment at all costs,” Whitman adds. “Geriatricians are at the forefront of having these conversations, asking the patient what’s meaningful for them and understanding the impact. Recovery time is hard. It’s really important to talk to patients and understand the implications for their independence.”

Part 2: Money Perceptions

We figure out how to live within our means. What choice is there?

Americans have become good at the psychology of money. Slightly more than half of people 70 and older view their financial situation as excellent or very good. These survey responses seemingly conflict with a mountain of data that shows how limited retirement savings are for average Americans.

One interpretation of this is that many older adults — such as 56-year-old Jackie — are simply mastering the art of living within their means. “I will have to live on a budget,” she says. “I don’t think I’ll ever be destitute or homeless. I have a big family that would always take care of me. I’ve been saving. Yeah, finances concern me because inflation’s going up. But I think I can manage it by being stricter and not being so loose with my wallet.”

Finances remain a big issue

While older adults may be fine with the current state of their finances, some do have concerns about the longer term. Although a minority, nearly 4 in 10 survey takers 60 and older say they are very or extremely worried that their money will not last. And only 16 to 18 percent of those surveyed reported significant improvements in their money situation over the past decade, despite Wall Street’s bull market.

“You can see the financial uncertainty,” says Peter A. Lichtenberg, director of the Institute of Gerontology at Wayne State University.

Younger adults don’t grasp the financial realities of retirement

Meanwhile younger adults’ expectations for how their retirement will be funded look different from the realities facing older adults today. For example, some 37 percent of younger survey takers say they don’t expect to rely on Social Security benefits when they reach retirement, while 94 percent of the oldest survey takers say they do rely on Social Security today.

Likewise, 63 percent of the youngest respondents in the survey expect to use their savings, which is something just 39 percent of the oldest are actually doing. And 24 percent of the youngest adults expect to use income from a part-time job in retirement, whereas only 8 to 15 percent of retirees 60 and older have part-time jobs.

“Most people in their 40s don’t understand how important Social Security will be by the time they’re 80,” Whitman says. “Eighty-one percent think they’ll use a retirement plan, but they overestimate paying for retirement themselves. Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid are so critical to our health and our financial security as we age.”

Part 3: The Pursuit of Happiness

Meet the happy realists

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that older adults in the survey make up the happiest age group. The U-curve model that depicts happiness has been widely reported: It starts high, when we’re young, hits a low in our late 40s and then begins a steady climb back up. Interestingly, though, when people 85-plus were asked to say what they considered the best decade of their lives, they most frequently cited their 50s.

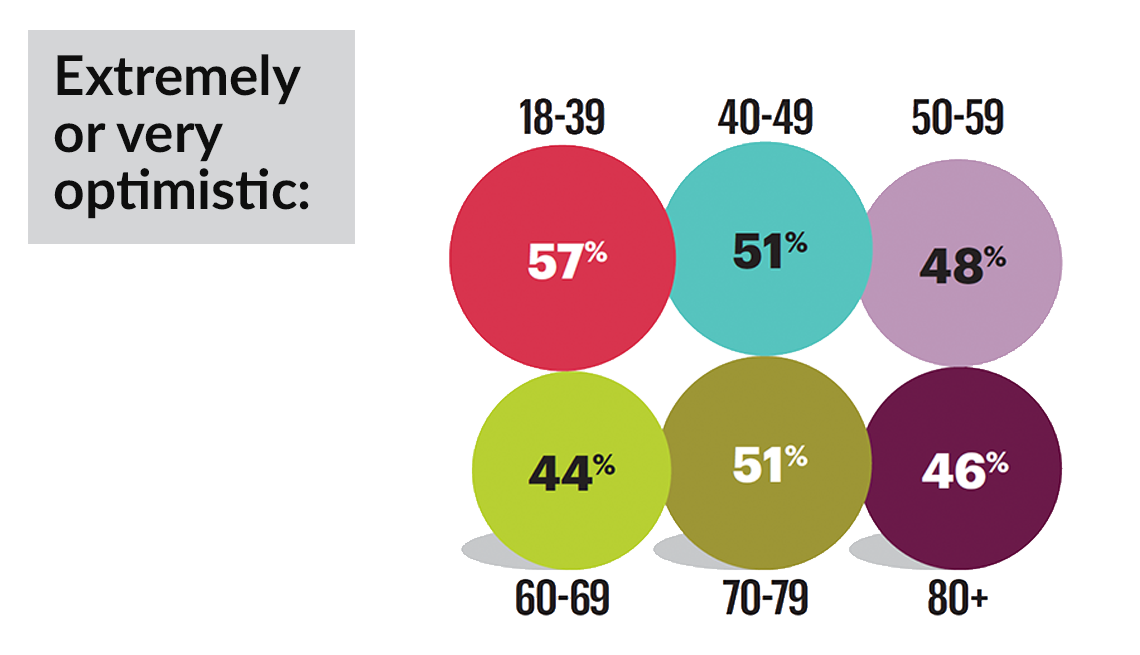

But the study also shows that optimism is lowest for those in their 60s and 80s. One way to look at that is lack of optimism equates to fulfillment. “I don’t look forward to anything new,” says nonagenarian study participant Ruth. “I love to watch the birds. I love to swim. I love to play Ping-Pong. It’s just more of what I already love.”

Respondents in their 40s and 50s reported lower happiness scores but higher optimism scores.

The power of simple goals

About 2 out of 3 of the oldest adults, age 80 and older, say they’re living their “best possible life” or close to it, compared with just 1 in 5 younger adults. What’s driving this remarkable shift? “Psychologically, people notice and prioritize the positive and let the negative go as they age,” says Louise Aronson, M.D., professor of geriatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, and author of Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life.

“It’s the ticking clock theory: We all have to die; as you get closer, you think, Hey, what really matters? When you’re young, you may think, I’m going to suffer now because it’ll be worth it later. But later, you realize none of that made me as happy as being with my family or taking long walks every day,” she adds.

As 70-year-old Richard, who is a retired financial planner, puts it: “I did what I did to make a living, and I enjoyed it. But once I walked away, I honestly didn’t miss it for 10 minutes. That’s not my identity. That’s not who I am. My wife and I are heavily involved in our church. We’ve done mission trips to Cambodia, to Rwanda, to Australia, to China — to help dig wells and build homes and those kinds of things. I consider that to be who we are.”

Is optimism a lifestyle?

Another interesting finding on optimism: Those with an optimistic outlook were twice as likely to be engaged in healthy behaviors as those with a pessimistic attitude.

“My research shows that positive beliefs about aging can act as a buffer against stress, bolster your sense of control over your life and even your will to live, and motivate good habits,” says Becca Levy, professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health.

Part 4: Relationships

Friends are great, but family comes first

At every age, family members contribute more to a person’s sense of joy and sense of purpose than friends do. “Family is the people you can rely on, the people who see you and accept you,” UCSF’s Aronson says. But she also points out that “family” can take on a broader definition for many people.

If you’re among the growing group of single older adults or if you find yourself low on close family, “think about turning friends into your chosen family,” she suggests. For younger adults, she adds, “Now is the moment to make connections — with people who can see you through the coming decades.”

Our relationships grow closer over time

There’s a steady linear increase in how we rate our close relationships over time. By age 80, 85 percent describe their human connections as excellent or very good — up from 56 percent before age 40. And most say they have been at the same level for the past five years.“I’ve been with people who are dying,” Aronson says, “and that’s what matters in the end.”

Part 5: Life Stages

Is 60 the new 40?

Midlife crisis, move over. Based on survey responses, our 60s is the watershed decade when it comes to the shifts in attitudes we’ve described about longevity, relationships, well-being and wealth. Concerns about life expectancy drop, while worries about stamina, cognitive skills, diminishing eyesight and memory loss peak. Our ratings of connection with friends and family rise. As noted, we get more serious about physical health, too.

“It’s a time that many people step back and say, ‘Oh, my health is not a given. I actually need to do things to at least make it stable and make it … better.’ I would say the peak time window that I see patients is between 50 and 70,” says Friedman, founding director of the lifestyle medicine program at University of Rochester-affiliated Highland Hospital.

For Richard, the wake-up call came when he saw a TV spot about an active older man in his industry. “While growing up, I remember life expectancy being 65. You retired at 65, you died at 67. It’s pretty much what it is,” he says. “Now, I’m 70, and life expectancies are closer to 80. But I remember seeing it happen to a portfolio manager, a mutual fund manager. A news show did a spot on him, and he was 70-something years old, still working out, still trim, still buff. And I said to myself, “Well gee, maybe I don’t have to die at 65. If he can do it, I can do it.”

Retirement Happens When You’re Busy Making Other Plans

Many older adults report they retired sooner than expected. While 57 percent of retirees in their 60s expected to clock in for the last time after age 65, in reality, 82 percent of them retired at age 64 or earlier. The fascinating exception: 20 percent in their 80s or older retired after 70. And 3 percent are still working and say they don’t know when they’ll stop.

“I think people find they need the money. But some feel, ‘I just want to do something and I might as well be paid,’ ” Wayne State’s Lichtenberg notes. While personal choice was the dominant reason for retirement at all ages, health reasons peaked in the 50s and 60s.

Afterward, many reveled in their freedom. “This is the time to try things that you never did before,” says Robin, 64. “I always said, ‘Man, if I could only sing, I would be a Broadway star.’ ... I can’t sing, but they do have a community theater here, and I’m going to try out for a role. But I could also work as a stagehand. This is the time to just have fun.”

Part 6: Our Final Years

Afraid of death? Nope. Ready for it? Maybe

“People aren’t afraid of death,” AARP’s Whitman says. Indeed, the survey shows such fear generally decreases with age. Of greater concern is controlling the circumstances. “People want choice and self-control when dying,“ she says. Most survey respondents endorse medical aid in dying.

Yet it’s not until their 80s that many people reported making necessary plans that will help their families and medical team understand and carry out their end-of-life wishes — as well as plans for their assets, funeral and burial.

Memo to your grown kids: You can relax

The study shows that we have more concerns about our future when we’re under 40 than we do in our 70s or 80s, be it about the risk of cancer, finances, life expectancy, emotional health or sexual performance. But the people in the study with the most real-life aging experience to draw on — those 85 and up — report that in almost every important category, life worked out just fine. Up to 90 percent say so about meaningful relationships, living arrangements, mental sharpness, finances and mobility.

Younger adults can cultivate positive attitudes toward aging by appreciating the strengths of the elders in their own lives, Yale professor Levy says. “Develop a portfolio of positive images of aging by using four examples of older people you admire.”

Christine, a study participant, is a great example. “I’m glad I’m here today,” she says. “I, of course, still have some health issues that irritate me. They get in the way of doing everything that I want to do. But few people at 73 are able to do everything they want to do. Of course, you got your standouts, the athletes or the joggers. No. I want to enjoy life, not kill myself trying to get through it. I want to be comfortable, with a roof over my head and food on the table, be able to travel, enjoy time with my husband.”

Ruth’s a great example, too: “Aging is aging. It’s something that happens. It can be good if you have a right attitude. It can be terrible if you resent it and think of all the aches and pains you acquire, which you didn’t used to have.” As the study shows, most of us choose the right attitude.